Henry was ill-prepared for the sight and unaccustomed to the odd sensations. He couldn’t have said if the sensations were warm or cold, if they comforted or inflicted—only that he was transfixed. He could not move.

She sat in the chair he usually occupied, with her elbows on the upholstered armrests, Peter in her lap, his fingers twirling one of her stray curls.

She did not fuss at him for it, nor did she even seem to notice. She read in tones soft, animated, as if the story had come alive to her. “‘For Dolly’s charms poor Damon burn’d. Disdain the cruel maid return’d: but, as she danc’d in May-day pride, Dolly fell down, and Dolly died—’”

“Died?” Peter leaned up.

“Died indeed,” echoed Miss Woodhart, brows raised theatrically.

With eyes wide and solemn, Peter settled back and listened.

Henry should have made himself known. He knew that. It was a breach of etiquette to linger in the doorway as a common eavesdropper.

But if there was comfort for him here, he could not disrupt it. He had always wanted his son to have the one thing he himself had never possessed—a mother’s love.

Yet that was the very thing he had ripped from Peter’s life. The very thing he could never give back.

“‘And now she lays by Damon’s side. Be not hard-hearted then, ye fair! Of Dolly’s hapless fate beware! For sure, you’d better go to bed, to one alive, than one who’s dead.’” A smile dimpled her cheek as if to soften the extremity of such a mature theme as death. Then her eyes lifted, roamed the room—paused and rounded.

Henry emerged from the doorway. “You have an impressive voice, Miss Woodhart.”

Peter climbed off her lap, and she snapped the book shut. “I was not aware I had an audience.”

Was she scolding him? He rather thought so. Didn’t the woman know her place? And for heaven’s sake, why was he not rankled by her unseemly candor? How odd that he should be amused by such a chit of a girl.

“Papa, it has stopped raining.” Peter tugged at his coat. “May I go out of doors?”

“I believe it would be in order to ask your governess.”

His eager grin turned toward Miss Woodhart. “May I?”

“Yes, and I shall go with you.”

He clapped his hands and squealed, but his spirits dampened some when Henry instructed him to return the book to the library first. He pelted from the room.

“And do not run in the house,” Henry shouted after him.

“I need not be in suspense as to why you are here.” Miss Woodhart remained seated, but her back arched and stiffened. “Though I do not know what I might do now, with the exception of apologizing.”

Henry stared at her. What was she talking about?

“Which I am very good at,” she added.

“Good at what, Miss Woodhart?”

“Apologizing.” Her head cocked. “But should you not first care to hear my opinion of the painting? I assure you, my lord, I shall not dare say she is solemn.”

Unease tightened around his throat. “It seldom matters to me what others think.”

“With my opinion falling among the least, I presume.” She glanced away for a moment, sighed, then returned her gaze to him with no small amount of prejudice. “My apologies nonetheless, my lord. It shall not happen again.”

Peter bounded into the room again panting for breath. She rose to greet him.

“Won’t you come too, Papa?”

He shook his head. “Another time.”

Hands clasped, Miss Woodhart and his son quit the room. The sounds of his happy chatter, the feathery trail of her laugh… They melted into a silence he knew all too well.

If only she would love his son. If only she would offer him what no woman ever had, a mother’s faithful heart.

Every little boy needed that.

Henry knew.

* * *

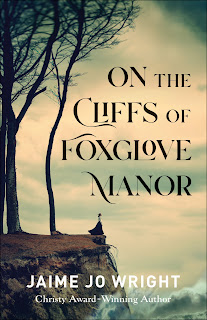

Ella shuddered and drew her wrapper tight around her. Thunder shook the sash window of her bedchamber. Lightning brightened the darkness, illuminating the raging sea—then the world plunged back into blackness.

How odd that she should desire to sit here, with her fingertips pressed against the cold glass, and her position so close to the turmoil outside. It was late enough that the house was doubtless asleep. She had no wish to prowl in the night, to venture out into passageways that were black and endless.

Yet it was something she must do. This was, after all, the reason she had come.

Taking her pewter candlestick, she slipped quietly into the hall. At various times when she knew herself to be alone, she had investigated all the rooms on this floor. She had discovered nothing. She had also searched below stairs, but since there were no bedchambers, she had found very little to interest her.

Thus, she approached the stairway and started up. The steps creaked beneath her, as if from lack of perpetual use, and the feeble candlelight invaded deep shadows.

She reached the landing.

Dark, empty space spread out before her, but she was not so afraid as to turn back. No. She most certainly would not do that. Courage was her virtue—wasn’t it?

She had great difficulty swallowing, but such could easily be explained, for the hallway was dusty and stifling. She padded to the first door and tested the knob. It turned with a small creak, but she hesitated. What if she stumbled into Lord Sedgewick’s chamber?

No, it was not possible. Lord Sedgewick was located in another wing of the house—Peter had informed her so. There was no chance she would be discovered. She had never seen anyone approach this floor, least of all the lord himself.

She pushed inside the room and swept around with her candle. Nothing. It appeared to be little more than an old guest room, long since abandoned if the dust was any indication.

She continued down the hall, opening doors, peering in alcoves, slipping in and out of shadowy places.

She entered another bedchamber and leaned inside.

Candlelight spread a glow across a canopy bed, a dressing commode, a Sheraton fire screen, a bookshelf…

Ella’s heart leaped to her throat. The bookshelf. Of course there would be one, of course it would be here. Lucy would dare not go anywhere without her volumes.

Ella’s hands shook as she approached. She brushed her fingers against the dusty spines, recognizing many of them, wondering why no one had missed them from her father’s library.

How Mother would have scolded her sister for taking them from the house. It was the only defiant thing Lucy had ever done in her life.

A roar split the air.

Ella jumped, whirled. Her heart settled when she realized it was only thunder. She was being as fearful and timid as Matilda. A smile upturned her lips at the thought, and she turned—

Movement caught her eye. Something small, then a rustling noise.

Her stomach lurched. Her flesh raised in goosebumps. With a throbbing chest, she lifted her candlestick.

Light cast itself into darkness. The bed was illuminated.

I have the greatest of imaginations. Sweat formed on her skin. It is only the storm—

The bed creaked, as if under a weight. The curtains rippled.

A scream lodged in her throat, but she flew away so quickly the light flickered into darkness. She darted into the hallway. She ran blindly, cupping her mouth. It wasn’t the storm.

She found her bedchamber and locked the door with her key. Dear heavens, it wasn’t the storm.

Chapter 5, Pages 60-64

.jpg)